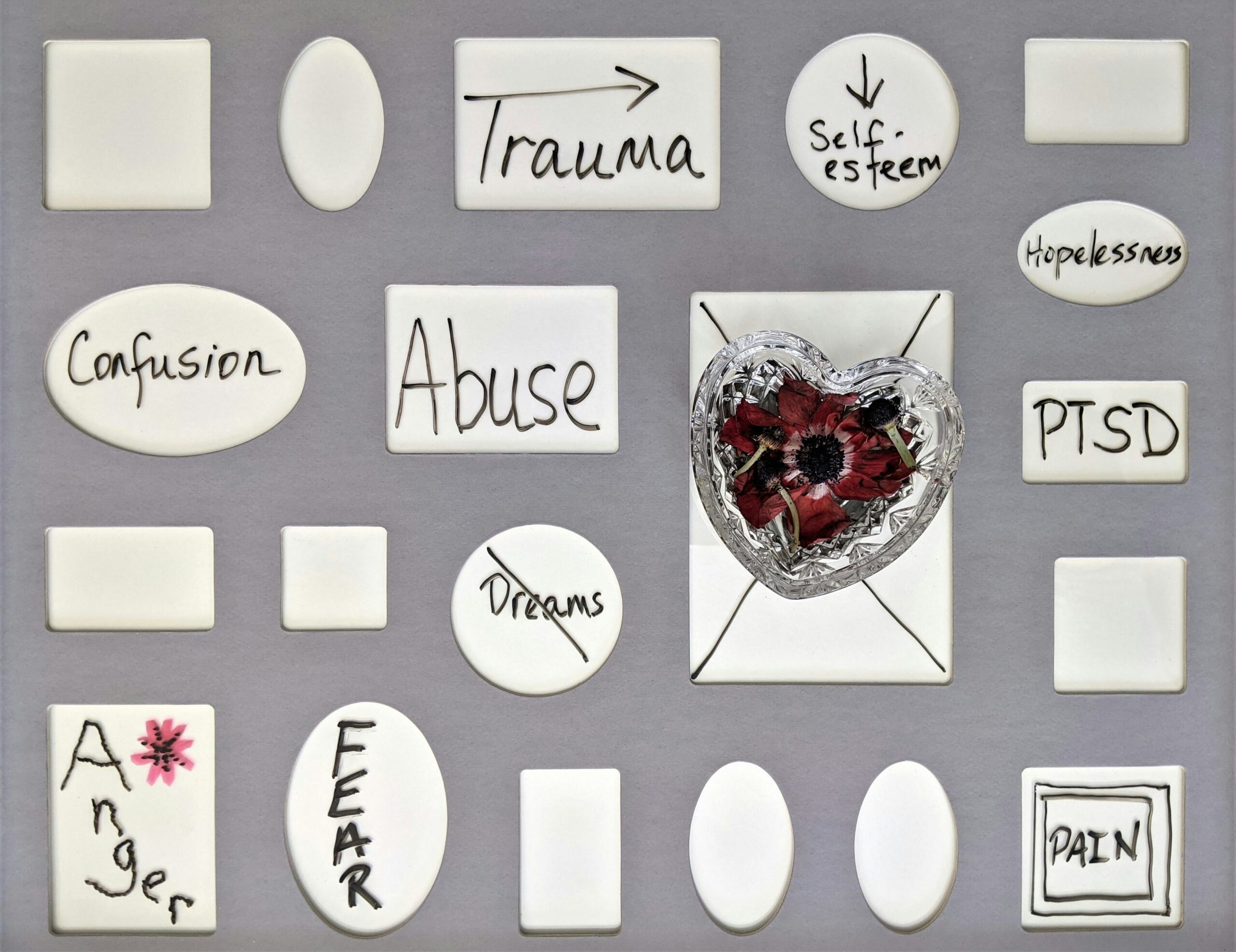

PTSD, Depression, and the Stories the Brain Tells to Survive

Memory doesn’t fail because someone is weak. It bends because the brain is doing its best to survive.

When trauma enters the picture—especially early trauma or unresolved grief—memory stops functioning like a clear timeline and starts functioning like an emotional map. This is especially true for people living with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, or a history of chronic stress. In these cases, memory becomes less about what happened and more about how it felt.

Research has shown that individuals with PTSD and depression are more susceptible to false memories when the information they are exposed to is emotionally charged or closely related totheir trauma history. In other words, the brain doesn’t distort memory randomly. It distorts memory in familiar emotional territory.

This matters, because trauma doesn’t just leave emotional scars—it alters how the brain processes, stores, and retrieves information. The hippocampus, which helps organize memories in time and context, can become less efficient under prolonged stress. Meanwhile, the amygdala, which detects threat and emotional significance, becomes more reactive. When these two systems fall out of balance, memories can become fragmented, overgeneralized, or emotionally intensified.

What often happens is this: emotionally negative experiences are remembered more vividly than neutral or positive ones. Details may blur, but the emotional charge remains strong. Over time, the brain may fill in missing details with information that feels consistent with the emotional memory, especially if that information is repeated, reinforced, or suggested by others.

A large body of research supports this. A comprehensive review published through the National Library of Medicine examined false memory effects in individuals with PTSD, depression, and trauma histories. The findings were striking. When participants were exposed to emotionally associative material—information that aligned with their existing emotional knowledge base—their rates of false memory increased significantly compared to non-traumatized groups. However, when the material was neutral and non-associative, this difference largely disappeared.

This tells us something important. Trauma does not make people unreliable across the board. It makes them more vulnerable when information touches emotional wounds that already exist.

Depression adds another layer. Depressed individuals often experience what researchers call “overgeneral memory.” Instead of recalling specific events, the brain stores broad emotional summaries. Pain becomes a theme rather than a moment. When new narratives align with that theme, they can be absorbed more easily, sometimes reshaping past experiences in the process.

This doesn’t mean trauma survivors are imagining things. It means their brains learned to prioritize emotional meaning over factual precision—because emotional meaning once kept them safe.

This is why memory conflicts can feel so devastating in families touched by trauma. One person may remember love, effort, and survival. Another may remember fear, absence, or pain. Both experiences can feel absolutely real to the person holding them. Trauma doesn’t just change memory—it changes perspective.

Understanding this doesn’t invalidate anyone’s pain. It doesn’t excuse harmful behavior or rewrite accountability. But it does offer a framework that replaces moral judgment with neurological understanding.

False memories are not lies. They are not intentional distortions. They are often emotional truths searching for context.

For those of us who carry gaps in memory, confusion about the past, or conflicting versions of shared history, this knowledge can be grounding. It reminds us that memory is shaped by the nervous system, by emotional safety, and by the stories we hear when we’re most vulnerable.

Healing doesn’t always mean recovering perfect recall. Sometimes it means learning to hold memory gently, with curiosity instead of self-blame. It means recognizing that survival reshapes the mind—and that understanding how memory works can soften shame, resentment, and confusion.

Memory is not evidence of failure. It is evidence of endurance.

This post may contain affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to you. I only recommend books that align with the heart and mission of LuvMyCrazy

📚 Helpful Books on This Topic:

Everyday Trauma-by: Tracey Shors

Memory, Trauma and the Spirited Life: Remembering and Identity-by: Gillian Burrell

Related Reading on LuvMyCrazy

To understand how memory reconstruction begins—especially in childhood and grief—read:When Memory Isn’t a Recording: How Trauma, Loss, and Influence Shape What We Remember

This peer-reviewed article explores false memories in PTSD, trauma, and depression:

👉 National Library of Medicine – False Memory and Psychopathology

If you or someone you love is struggling with grief or loss, you’re not alone. There are organizations that offer free support, guidance, and community: #988